Introducing the camps

The Bhutanese refugees first entered Nepal at the end of 1990. Temporary camps were established on the banks on the Mai river. Disease and squalor were rife.

UNHCR began providing ad-hoc assistance to Bhutanese asylum seekers in February 1991. By September 1991, there were approximately 5,000 refugees when His Majesty’s Government of Nepal (HMG-N) formally requested UNHCR to co-ordinate all emergency assistance for the Bhutanese refugees. UNHCR, the World Food Program (WFP) and several Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) launched a major program in the early part of 1992.

WFP, UNHCR and partners provide food, water, shelter, health, education, protection and other ‘non-food’ items. The established health and nutrition indicators suggest that the assistance has been adequate and, in fact, exceeds the national standards for Nepali citizens.

The seven Bhutanese refugee camps are located throughout the Jhapa region of the east Nepali terai (sub tropical lowlands), adjoining the foothills of the Himalayas.

The climate is hot and humid, with heavy rains in June and July. In spring, the mountain melt water means that flooding is common.

The structural layout in each camp is very dense, with shelters often under one metre apart. Fires occur frequently and can be very destructive.

There is little violence within the refugee population, and community committees undertake much of the everyday management of the camps.

Refugees and the local population compete for some environmental resources, such as the collection of dead wood for fuel and the supply of bamboo for construction.

Relations are relatively good, however, with some locals taking part in camp management.

The sites are all located on government forestry department land. Many large saal trees were cut down to provide space for the building of huts.

Flood protection was required on some sites, but the engineering works undertaken have not proved wholly successful.

Construction materials and perishable foodstuffs are sourced regionally, but without sustainable strategies. Locals have complained that wells near some camps have run dry, as a result of over-extraction and ‘draw down’ near refugee wells.

The camps and their populations

CAMP POPUlation No OF Families No of HUts PEople per hut

Beldangi-1 18,335 2524 2843 6.45

Beldangi-2 22,542 3358 3604 6.25

Beldangi-2 extension 11,594 1672 1827 6.35

Goldhap 9,513 1348 1511 6.30

Khudunabari 13,392 1960 1960 6.83

Sanischare 20,993 2790 3212 6.54

Timai 10,293 1382 1716 6.40

TOTAL 106,662 15,034 16,673 6.40

Camp population figures in 2006

Orgs working in the camps

UNHCR is responsible for the overall co-ordination of the camps. They subcontract to a number of agencies and organisations listed below to provide food and essential services in the camps.

UNHCR United Nations High Commission for Refugees

Currently, the overall responsibility for the maintenance of camps lies with UNHCR.

WFP World Food Programme, a United Nations agency. Provides food aid.

LWF Lutheran World Federation

LWF Nepal was the first organisation extending humanitarian assistance to the Bhutanese refugees. Initially, LWF Nepal established systems for all key needs and later handed over some services like health, distribution of food and non-food items and logistics when UNHCR and other NGOs arrived on the scene in response to the continuing arrival of new refugees.

LWF, as an implementing partner of UNHCR, has been responsible for care and maintenance of shelters, service-centres, water supply and sanitation and community services activities for the refugees. Since January 2006, LWF has taken over the responsibilities for the distribution of food and non-food items, including vegetables for the refugees, upon the request of UNHCR and WFP.

THE NEPAL RED CROSS Distributed food and other essential rations until the beginning of 2006 when LWF took over.

CARITAS (Nepal) Since 1992, the UNHCR has delegated responsibility for secondary and higher secondary education for refugees to CARITAS (Nepal) under the management of the Jesuit Refugee Service, South Asia. There are over 35,000 pupils and 700 teachers in the refugee schools. The programme is run almost entirely by Bhutanese, with a small number of Nepali staff.

THE NEPAL BAR ASSOCIATION Provides legal counseling and legal representation for victims and alleged perpetrators of serious crimes, including gender-based violence.

AMDA Association of Medical Doctors of Asia. Provides primary health care.

OXFAM OXFAM Nepal organised non-formal adult literacy and pre-school education classes for the refugees from 1992-1996 before withdrawing from the camps. It also initiated community-based income generation programmes and rehabilitation programmes for people with special needs.

SCF UK Save the Children UK

From 1992 until 2002 SCF UK provided basic health care to the refugees and looked after preventative care and health education. They also established the original Children’s Forum Project (link to The Children’s Forum) for the young people of the camps.

THE CENTRE FOR VICTIMS OF TORTURE NEPAL (CVICT) In 1995 and 1996 CVICT initiated programmes of occupational therapy and medical counselling for those traumatised by violent experiences in Bhutan.

Refugee-run organisations

BRAVVE Bhutanese Refugee Aid for Victims of Violence

BRWF Bhutanese Refugee Women’s Forum

Refugee women’s organisation focusing on income generation, health and women’s rights, with representation in all 7 camps

Refugee huts are arranged in lines and made of plastic and bamboo. Pasang / PhotoVoice / LWF

We have lots of football tournaments in the camps. Pasang / PhotoVoice / LWF

Friends in the classroom. Aite Maya/ PhotoVoice / LWF

We make an effort to keep our school uniform looking smart and tidy. Ajay / PhotoVoice / LWF

The water taps near by hut. Madan / PhotoVoice / LWF

Children in the camps play lots of games that we did not know in Bhutan because we lived far away from each other. Madan / PhotoVoice / LWF

Structures in the camps

Camp organisational structures

At a camp level the day-to-day running is carried out through a system of committees.

Refugee Coordination Unit (RCU) - The Refugee Coordination Unit (RCU) is the Nepalese government authority in Jhapa and Morang districts that implements all government policy in the seven camps. RCU offices are stationed in each camp to oversee administration. Two Nepalese government officials staff each camp, and the district-level RCU office is based in Chandragadhi, Jhapa district.

Camp Management Committee (CMC) - The camp management committee (CMC) is the refugee-run administration in the camps. The CMC is headed by the camp secretary and is made up of representatives from each sector in the camp. The CMC has committees that coordinate birth and death registrations, food distribution, and health programming, and that determine responses to social problems, such as disputes within families or between neighbours.

Camp Secretary - The head of the camp management committee in a refugee camp. The camp secretary is elected by the refugees.

Sector Head - The sector head is an elected member of the refugee-run camp management committee. The sector head is responsible for addressing problems in his or her sector, usually comprised of two to five sub-sectors. He or she forwards unresolved cases to the camp secretary or RCU.

Counselling Board - The counselling board is made up of elected representatives from the CMC. The counselling board serves as a community justice mechanism to resolve day-to-day problems and disputes in the camps.

Education

The refugee community played a central role in setting up their own education system when the camps were first established. Even during the dreadful days at Mai riverbank, before formal camps were set up, Bhutanese teachers, students and parents wanted education for their children. High school students and teachers volunteered to organise classes of over 100 pupils, anxious that the education denied to them in Bhutan should not be lost forever.

The English medium education programme is currently run almost wholly by Bhutanese,teachers and staff with a small number of national resource and management staff. Schools in the camps cater for classes through from pre-primary level to Class X. Classes taught range from the traditional subjects to Dzonkha (the Bhutanese national language). For higher level education (Class 11 and 12 and university) students go to study outside the camps. There is a very limited number of scholarship funds available for further studies and most young people and their families have to find a way of self -funding their higher education, covering the cost of school or university fees, books and living expenses.

In the camps schools pass rates have in general been high but recent statistics suggest that the standard has begun to slip. In the year 2004-5 2547 pupils sat their Class X exams with 2402 passing, giving a pass rate of 94%. In 2005-6 1621 out of 2320 pupils passed their exams, a pass rate of 70%. This drop in standards is the result of an increasing lack of quality teaching staff as more and more Bhutanese have felt obliged to seek better paid employment teaching in private Nepali schools.

Camps teachers are paid a basic incentive salary whereas teachers working outside the camps earn at higher levels enabling them to provide support to the rest of their families. The current teacher turnover rate in the camps is at an all-time high.

As of the 30th November 2006 the number of students attending schools in the camps was 37,403.

Huts and sanitation

Some16,673 low-cost, temporary shelters, made from local materials with an expected lifespan of three years house over 106,000 refugees in seven camps.

Though the camps are now more than ten years old, the demand that structures should only be temporary meant that school buildings and even health posts inside the camps are constructed from flimsy bamboo.

One latrine is provided for two households a few meters away from their dwellings to allow them easy and safe access to latrines with privacy.

The latrines are equipped and ventilated with double pits. When one of the pits is filled, the refugees switch to the other pit with the ventilation pipe.

Sanitation volunteers also assist in repair and maintenance of the latrines. Bamboo and roofing material are provided to refugees and they themselves carry out the repair works on voluntary basis.

The refugees live in very cramped conditions yet despite this the water and sanitation facilities are of a good standard.

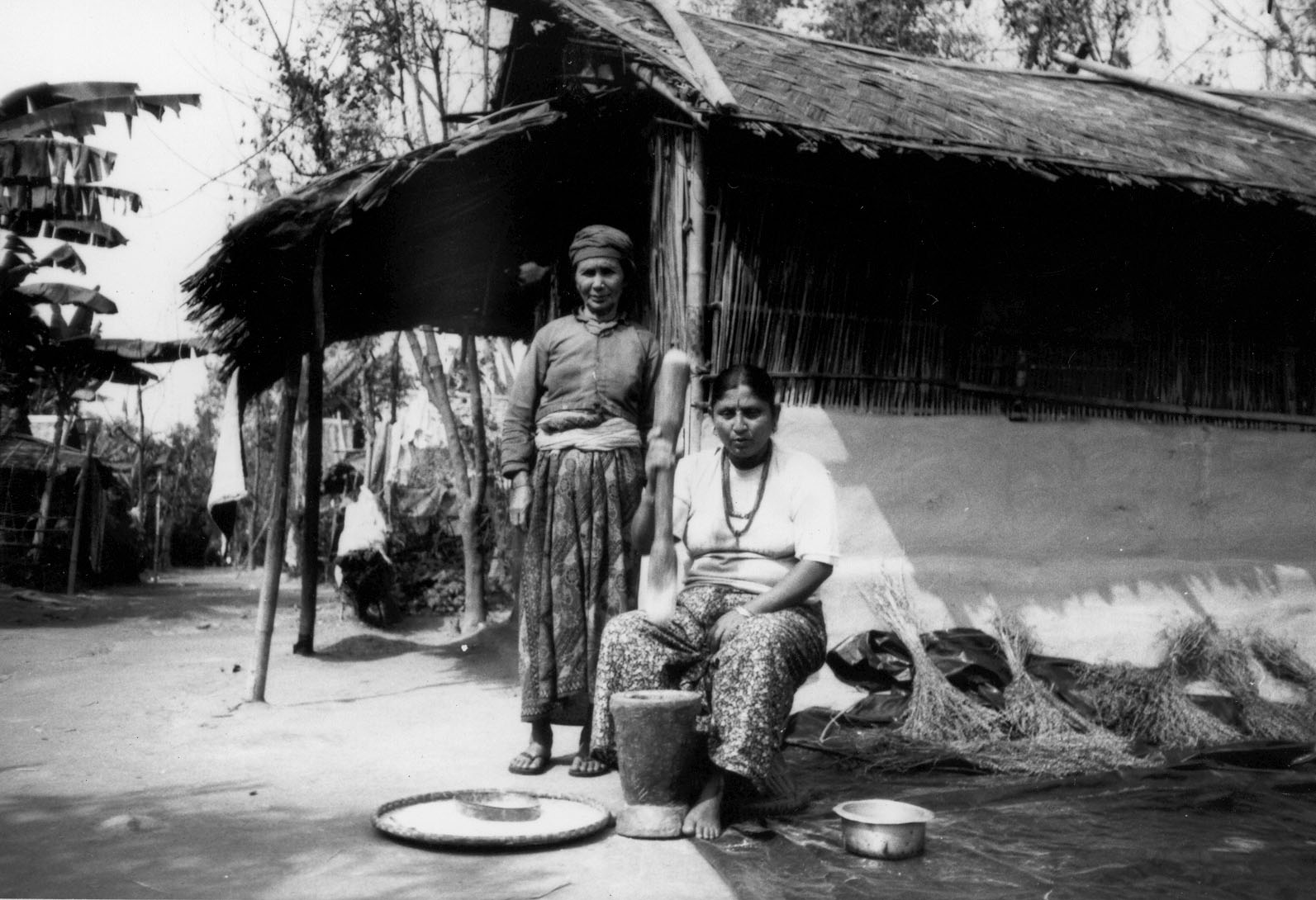

Winnowing and cleaning the rice. Bhimma / PhotoVoice / LWF

Supper in my hut. Yethi Raj / PhotoVoice / LWF

Bishnu Maya / PhotoVoice / LWF

Re-building huts. Dil / PhotoVoice / LWF

There are temples situated all over the camps. Khem / PhotoVoice / LWF

Refugees are poor in wealth but rich in kindness, helpfulness and ability. Yethi Raj / PhotoVoice / LWF

We are always thinking of Bhutan. Ndr Bdr / PhotoVoice / LWF

Work

The refugees, as per the policies of Government of Nepal, are prohibited from engaging in economic activities outside the camps. Unlike the Tibetan refugees in Nepal who have been granted refugee status that allows them to seek employment, Bhutanese refugees are forbidden from working outside the camps.

However, there are various opportunities for employment. Within the camps a number of adult refugees are paid incentive salaries at a fraction of average pay.

Due to the high standard of education, many young Bhutanese find teaching work throughout Nepal, although they hide their refugee status.

Others find work as labourers in industries such as road-building, stone-breaking and agriculture in order to supplement their families’ meagre income.

Due to donor fatigue and subsequent aid budget cuts a large proportion of the young have been compelled

In recent years rations have not included vegetables or clothes.

Many are also forced to work outside the camps in order to fund their further education.

Food and rations

Food rations are distributed every two weeks. Rations are distributed to each household in proportion to the number of members in the family. There is no variation in quantity according to age; a full grown man receives the same amount as a toddler.

Refugees receive a ‘food basket’ containing rice, lentils, vegetable oil, sugar, salt, wheat soya blend and some vegetables. Over recent years the provision of vegetables provided has been gradually reduced forcing people to earn an income to buy food to supplement their rations and to ensure that their diet remains healthy.

Refugees are also provided with non-food items. However, rationing of these basic materials has decreased dramatically in recent years. Clothes have not been distributed for a number of years. The provision of bathing soap also was discontinued as of January 2006. Kerosene, used for cooking and lighting, was suspended at the end of 2005 and replaced by briquettes but this move had a big impact on the refugees. The briquettes burn slowly, produce a foul smoke and cannot be used as lighting fuel, thus preventing children from studying after dark.

Rations were distributed by the Nepal Red Cross Society (NRCS) until January 2006 when LWF took over. A community-based approach is used for the food distribution. Refugees themselves are directly involved in the fortnightly distributions under the supervision of a distribution sub-committee and LWF.

Water

The water system is managed centrally and operated by incentive workers. In all seven camps the water system is centrally controlled and distributed through pipes. The water is pumped from deep wells by diesel engines to overhead tanks where the water is then chlorinated and subsequently distributed through pipes two to three times per day to tap stands located throughout the camps.

Water taps are located through out the camps and a number of huts share a single tap. The water comes on for a few hours twice a day in the morning and afternoon and is transferred from the taps to the huts in an assortment of plastic and metal containers

The approximate quantity of water is within established guidelines, i.e. 20 – 25 litres per person per day.

Psycho-social issues

Depression, suicide, alcohol and drug abuse, dropping out of school, domestic and gender-based violence and trafficking in girls have all escalated in the camps. There were 159 cases of sexual and gender-based violence reported to UNHCR in 2005.

Anxiety and depression increase once children reach their final year of education in the camps, a time when they begin to think about how they will support their families.

CARITAS (Nepal) has been documenting ‘vulnerable’ cases, particularly orphaned children who have been left to fend for themselves through suicide or abandonment by their parents. In many cases, the eldest sibling – who has to care for younger ones – feels the most pressure and is, therefore, most susceptible to emotional problems.