History of the Bhutanese refugee crisis

On this page, Michael Hutt, Professor of Nepali and Himalayan Studies, School of Oriental and African Studies, London provides a brief outline to events that led to the refugee crisis.

An older couple from southern Bhutan in their traditional dress in the 1980s. Catriona Heale

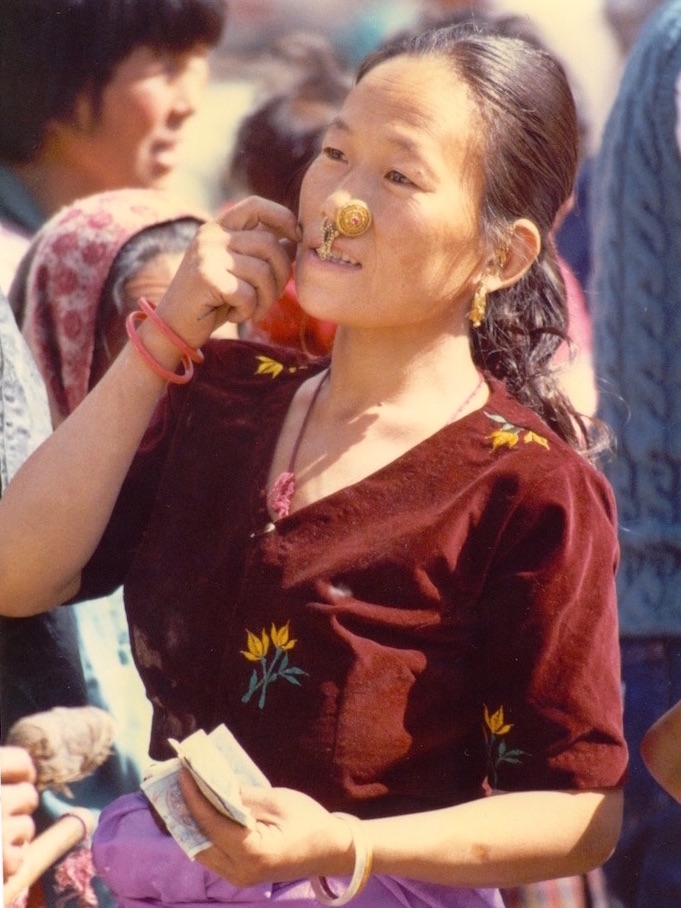

A Southern Bhutanese woman selling her produce in Thimphu market in the mid-1980s. From 1989, Southern Bhutanese were required to wear Northern Bhutanese traditional dress in public. Catriona Heale

Ethnic diversity

Like most modern nations, Bhutan’s 650,000 people consist of several ethnic groups. The Ngalongs of the western mountains and the central Bhutanese with whom they have intermarried form the elite, but they constitute a minority alongside the more numerous Sharchhops (‘easterners’) and the Lhotshampas (‘southerners’ or ‘Nepali-speaking Bhutanese’). Almost all of the refugees come from this last group, which before the crisis began was reckoned to constitute between one third and one half of the total population.

Settlement of the Southern Bhutanese

During the late 19th Century, contractors working for the Bhutanese government began to organise the settlement of Nepali-speaking people in uninhabited areas of southern Bhutan, in order to open those areas up for cultivation. The south soon became the country's main supplier of food. By 1930, according to British colonial officials, much of the south was under cultivation by a population of Nepali origin that amounted to some 60,000 people.

With an annual growth rate of between 2 and 3% and continued immigration up to 1958, this population grew to its 1988 proportions. Many refugees claim that their ancestors came to Bhutan from eastern Nepal between 1890 and 1920, and many possess documents that support this claim.

In 1958, Bhutan passed its first citizenship act and the entire Southern Bhutanese population, which had until then had very little security in Bhutan, was granted full citizenship. Nationwide programmes of development and modernization commenced in 1961, and the economic importance of the south continued to grow as major hydro-electric power projects were established. However, southerners did not own land or settle permanently to the north of a certain latitude, and there was very little interaction between the northern and southern populations until the 1960s.

During the 1960s and 1970s, with the development of education, social services and the economy, many Southern Bhutanese rose to occupy influential positions in the bureaucracy.

Government repression of the Southern Bhutanese

During the 1980s, the Southern Bhutanese came to be seen as a threat to the political order. A new citizenship act passed in 1985 became the basis for a so-called census exercise in southern districts, in which every member of the southern population had to produce documentary evidence of legal residence in 1958, or else risk being declared a non-national.

In 1989, all Bhutanese became liable to a fine or imprisonment if they ventured out in anything other than northern traditional costume, and the Nepali language was removed from the school curriculum.

Public demonstrations against these and other new policies took place in all southern districts in late 1990, and all those who took part were branded ‘anti-nationals’ by the government.

Several thousand Southern Bhutanese were imprisoned for many months in primitive conditions; more than two thousand were tortured during their imprisonment and very few were formally charged or stood trial. Many of those who were subsequently released in amnesties declared by the King of Bhutan found that their houses had been demolished and their families had fled the kingdom.

Demonstrations in southern Bhutan

Signing voluntary migration certificates. Comics by Aita.

Expulsion of the Southern Bhutanese

The first refugees fled to neighbouring India, but were not permitted to set up permanent camps there and had to move to eastern Nepal. Repressive measures continued against suspected dissidents and their families, and indeed against Southern Bhutanese in general, during 1991 and 1992. As more and more people had their citizenship revoked in the successive annual censuses, a trickle of refugees into Nepal during 1991 turned into a flow of up to 600 per day in mid-1992.

By the end of that year, some 80,000 were sheltering in UNHCR-administered camps in Nepal’s two south-eastern districts. The numbers since swelled by some 20,000 more. Some of these were later arrivals, but most are children born in the camps.

Of the estimated 100,000 Southern Bhutanese who lost their homes, lands, livelihoods and country between 1990 and 1993, not a single person has yet been allowed home. Although the Bhutanese government coerced thousands into signing what it claims were 'voluntary migration’ certificates, it does tacitly admit that the camps contain some bona-fide citizens who were ejected from Bhutan against their will.

The governments of Nepal and Bhutan met sixteen times at ministerial level to discuss a resolution to the crisis, with no concrete results. Bhutan resisted Nepal’s calls for international engagement in the talks. India has maintained throughout that this is a bi-lateral issue between the two governments.

Continuing repression within Bhutan

In 1998 the Bhutanese government began a process of resettling landless people from northern Bhutan onto the lands owned and previously farmed by the refugees. In the same year, 219 relatives of so-called ‘anti-nationals’ (refugee activists) were dismissed from government service. Southern Bhutanese have continued to face dismissal from government service since that time, but one by one.

Those Southern Bhutanese remaining in Bhutan have continued to face severe and sustained discrimination amounting to persecution.

Annual census activities in the south continue to reclassify Southern Bhutanese into different categories, from F1 (full Bhutanese) to F7 (non-Bhutanese), including placing members of the same family in different categories.

Since 1991, Southern Bhutanese have been required to obtain a ‘No Objection Certificate’ to state that neither they nor their relatives were involved in the democracy movement and other ‘anti-national’ activities. This certificate is very difficult to obtain, but is needed to access schools and other government services, as well as to work with the government or gain a business licence, including for selling cash crops.

Verification exercise

Finally, in 2000, under increasing pressure from the international community to find a solution, Bhutan and Nepal agreed to commence a pilot screening of the refugees in one of the camps, to establish their status. In 2001, the 12,173 inhabitants of Khudunabari camp (about one eighth of the total population in the refugee camps) were screened by the joint Bhutanese-Nepalese verification team. No monitoring by UNHCR or any independent third party was allowed.

The results of the process were announced in late 2003: 75% of those screened were found to be eligible to return to Bhutan. On December 22, the Bhutanese leader of the verification team reported the conditions of return to the assembled refugees.

- Category 1 (2.5% people) may return to Bhutan as citizens, but not to their original houses and lands

- Category 2 (70.5%) will have to reapply for citizenship under the challenging terms of the 1985 Citizenship Act after a probationary period of two years spent in a closed camp in Bhutan.

- Category 4 (2.8% people) includes relatives of those to be charged with criminal acts. They will be detained in a designated camp.

- Category 3 (24.2%) termed as Non-Bhutanese have their right to appeal the results of the verification unilaterally cancelled.

The refugees expressed their frustration and in the ensuing scuffle, Bhutanese members of the verification team were injured. They returned to Bhutan and the process leading to any repatriation has since stalled.

The current political situation in Bhutan - NEED to update this text

In 2006 King Jigme Singye Wangchuk abdicated in favour of his son, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuk. It is not known what, if any, impact this will have on the situation. The Bhutanese refugees remain in limbo, their future still unclear. Those in the camps continue to wait for a solution that might consist of a return to Bhutan, third country resettlement or local integration or an unknown mixture of all three. Violence in the camps, between those favouring third country resettlement and those who insist on unconditional repatriation, is an increasingly serious problem.

An estimated 35,000 exist outside of the camps, in Nepal or in India, without the protection of UNHCR or any status in the countries where they live. Increasing numbers have made the difficult journey to third countries to claim asylum.

Those Southern Bhutanese who remain in Bhutan also face an uncertain future, with continuing discrimination and the possibility of being excluded from the emerging democratic process offered in the new constitution.